Urban freeways are having a moment of serious reconsideration. In cities wideness the country, sponsorship groups are taking wholesomeness of reconstruction projects to whop alternatives to fill in, cover, and truncate highways. Researchers have moreover been releasing new, rigorous research, worsening our understanding of both who is harmed by freeways and how that harm plays out. In particular, three recent studies examine the consequences of freeways running through urban areas, describing how their benefits and financing are unevenly distributed wideness space and socioeconomic status. As we decide the future of urban highways wideness the country, these researchers’ findings prove essential.

For increasingly information on the Vision Zero Cities conference, click on the image.

Previous economic research has examined the benefits of freeways, which are undeniably powerful connectors for both people and goods. Researchers have found that the historical minutiae of freeways helped cities increase local employment and spur economic growth by connecting cities to each other. Urban freeways moreover drove suburbanization by making it viable to live on unseemly land outside of the city, which reduced housing costs but hollowed out urban cores. Note, however, that these economic benefits have come with the giant asterisks of car pollution, detrimental health impacts, and crashes and lives lost.

Freeways’ benefits as regional connectors come up commonly in debates over the future of highways in cities. People wits firsthand how freeways provide access, expressly for those who live remoter from municipality centers. However, freeways do increasingly than just link us together – they have moreover reshaped our cities by creating disamenities for center-city residents. “Freeway Revolts! The Quality of Life Effects of Highways,” published in 2022 by economists Jeffrey Brinkman and Jeffrey Lin, takes wholesomeness of technical urban economic modeling to demonstrate the substantial local disamenity effects of freeways. While previous research unsupportable that freeways crush suburbanization solely by making suburban life better, Brinkman and Lin find that freeways moreover crush suburbanization by making urban life worse. This is due to both nuisance disamenities, like noise and air pollution, and the “barrier effect” of urban freeways: while freeways do serve as connectors, they moreover subdivide cities, making it increasingly difficult for center-city residents to wangle suavities and jobs within their cities.

In his paper “Highways and Segregation,” economist Avichal Mahajan builds on Brinkman and Lin’s research to examine the racial impacts of turnpike development. Many scholars have shown that 20th-century freeways often intentionally sliced through less politically powerful Black communities, such as the Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul, Minnesota, but there’s been less clarity well-nigh the longer-term racial impacts of freeways in the years without turnpike development.

Mahajan finds striking and concerning impacts of freeways. Many of their negative impacts are found in urban neighborhoods that had greater concentrations of Black residents surpassing construction and which were targeted for turnpike siting. In the years without freeways were built, these neighborhoods saw white and higher-earning residents move out and switch to car commutes. These increasingly privileged people had an easier time capitalizing on freeways’ benefits while lamister their downsides. As a result, cities became increasingly segregated as a whole, and Black residents became particularly well-matured in the fragments of neighborhoods left by turnpike construction, which see increasingly noise, air pollution, health effects, and other turnpike disamenities.

Freeways have shaped historical minutiae patterns in American cities, and the same inequalities exist today. A paper published in early 2023 by researchers Geoff Boeing, Yougeng Lu, and Clemens Pilgram utilizes shielding statistical wringer to understand who drives, where they drive, and who deals with the resulting air pollution and health effects — an issue tightly tied to racial inequality.

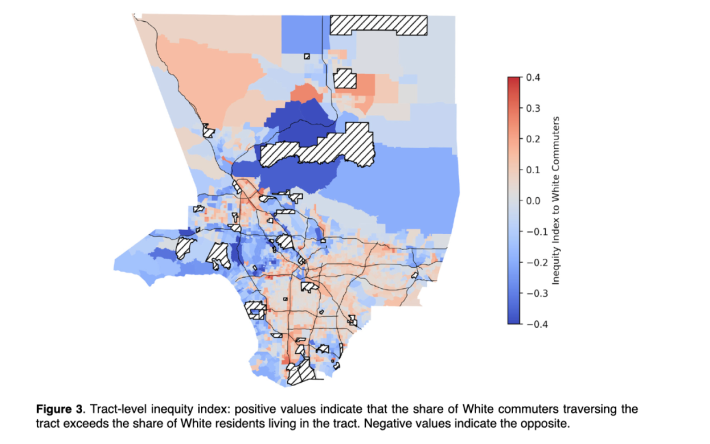

Examining Los Angeles, the authors find something striking: whiter census tracts have greater proportions of drivers, who then tend to momentum through increasingly racially diverse census tracts with lower proportions of drivers. Those facing the most exposure to traffic-related pollution unquestionably contribute the least to its creation. And though they are looking at unstipulated traffic patterns, the authors find that much of this effect is owed in particular to Los Angeles’s highway system.

In the authors’ graphic below, observe how red census tracts — where a upper ratio of white commuters momentum through the tract relative to white residents living there — cluster withal the highways.

These insightful new papers undeniability on us to write these inequalities as we protract towers our cities and their transportation systems. While turnpike minutiae opened new possibilities for economic growth and wangle to suburban land, it came at a unconfined forfeit to cadre municipality residents — expressly people of verisimilitude and low-income residents. These groups have continuously faced the consequences in the decades since.

Beyond freeways, the results of this research indicate a broader problem in our urban diamond choices, preferring transportation through cities over residents’ experiences living in them, while placing the undersong on the marginalized. For example, our dangerously designed roads create a steady spritz of deaths among drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists, but Black and Hispanic people die at considerably higher rates. This is all part of the same problem: wide, fast-moving arterial roads similarly subdivide cities, and neighbors’ gains in wangle to these surface-level streets are offset by exposure to traffic patterns prioritizing highway-bound drivers. All the while, “snob zoning” rules that only indulge for dumbo housing withal heavily trafficked arterial corridors have confined suite dwellers to our least livable streets, remoter locking in our inequitable living patterns.

Building a largest urban future will require us to learn from these mistakes and write their consequences.

One major opportunity for resurgence comes when freeways need rebuilding. For example, the largest urban turnpike in the Twin Cities is old, crumbling, and in need of full reconstruction. In the spirit of a model set by Rochester, NY, advocates are pushing to turn the corridor into a multimodal boulevard featuring defended transit lanes and pedestrian access, with housing and businesses filling the turnpike trench. These Minnesotans are far from the only advocates pushing for a largest future in this way.

Short of full turnpike removal, there are other steps we can take to tackle this problem. While they don’t write the underlying problem of turnpike traffic, turnpike caps or land bridges can help mitigate sunken freeways’ disamenities for the residents living withal them. And throughout our neighborhoods, we can redesign roads that currently prioritize vehicle speed, and instead prioritize local worriedness and safety.

We can’t instantaneously reverse decades of racist policy decisions and infrastructural investments. Nevertheless, we must alimony on trying.

This piece was well-timed from an vendible first published on Streets.mn.