As the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law continues to dump billions into state transportation budgets, a new scorecard ranks which states are most likely to use that money to reduce emissions and make roads increasingly equitable — and which are only making matters worse.

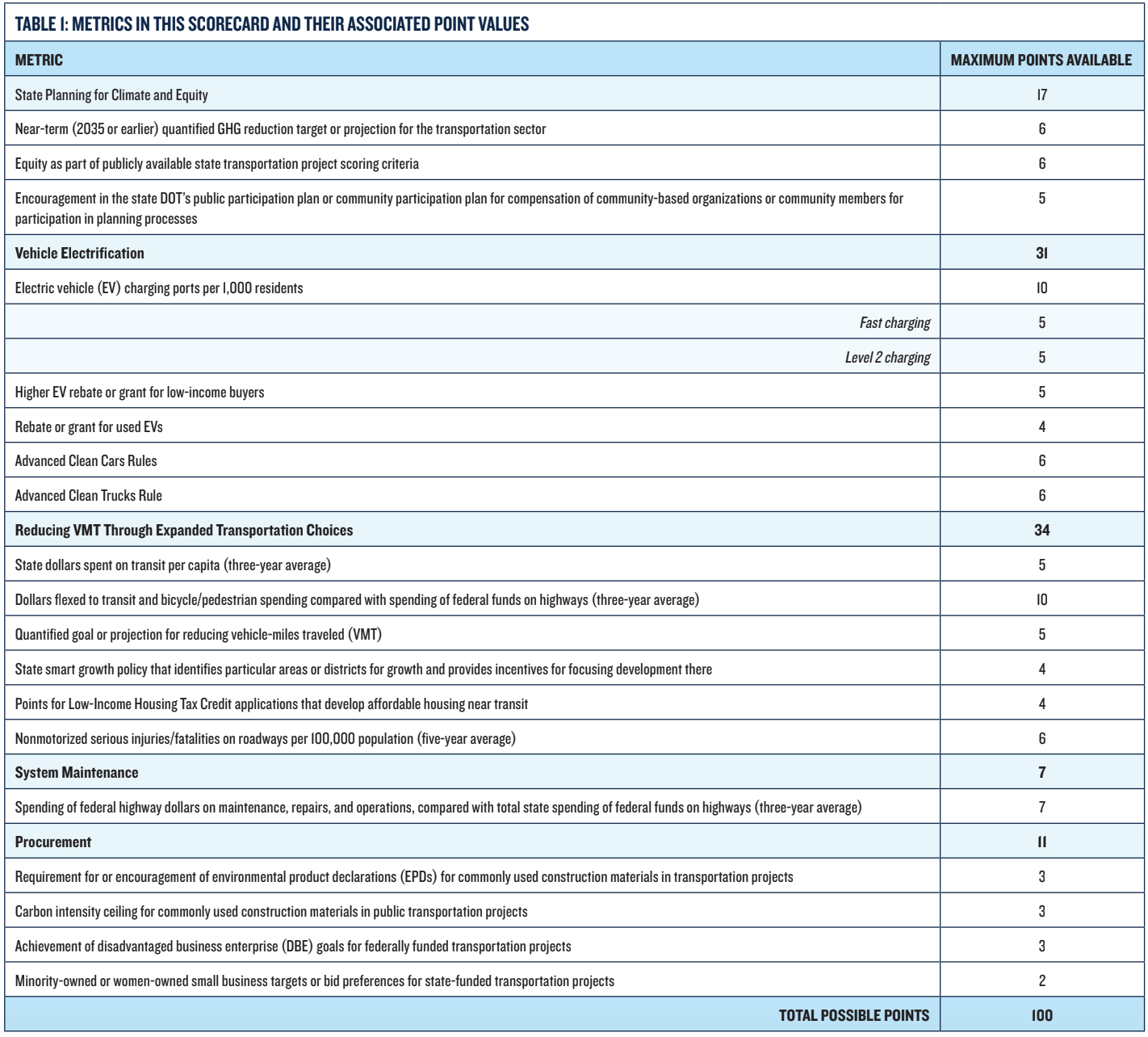

In a new report, the Natural Resources Defense Council ranked the transportation policies of all 50 states based on 22 probity and environmental metrics, such as how much money they’ve spent on transit in the last three years per capita, whether they’ve set would-be goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles (if they plane bothered to set a goal at all), and whether they’e taken steps to incentivize housing developers to build near transit lines or not.

Few Americans may plane know well-nigh those sort of wonky policies, but the report authors explain that they have massive implications for our everyday lives — especially in the wake of the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which nearly doubled the value of largely unrestricted mobility money that flows from Congress to the states every year. That spout of cash, though, could moreover be the perfect opportunity to step out of the “well-worn grooves” that policymakers have fallen into over the years, and finally whittle a new path.

“We’re spending increasingly money than we’ve spent on transportation than we have in several decades,” explained John Bailey, NRDC’s senior state and federal transportation well-wisher and the co-author of the report. “While the feds write the checks, the states are the ones in the driver’s seat when it comes to making decisions well-nigh how the money is sent. … If we spend increasingly money on the same kind of projects we’ve been towers for decades, we’re going to get the same bad outcomes. And ultimately, that’s up to the states, not Congress.”

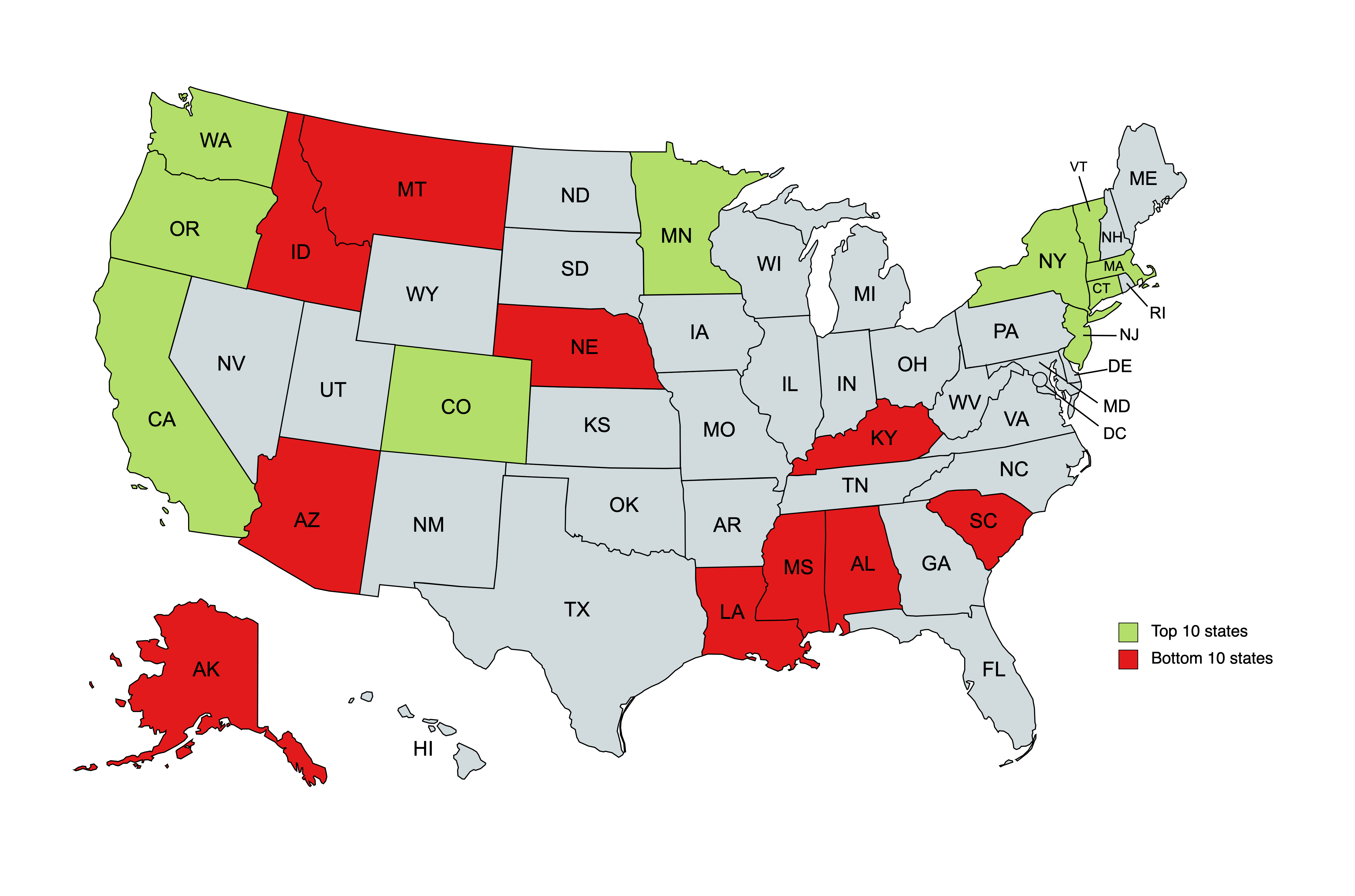

California, Massachusetts, Vermont, Oregon, Washington, New York, Colorado, New Jersey, Connecticut and Minnesota all ranked in the NRDC’s top 10, with the Golden State ultimatum the top spot. Kentucky, meanwhile, ranked worst, followed by Louisiana and Nebraska, which tied for second-to-last, and Alabama, South Carolina, Arizona, Idaho, Alaska, Montana and Mississippi, in descending order.

To get at least a unstipulated snapshot of how seriously state DOTs are taking the intertwined climate and probity crises that are roiling U.S. roads, Bailey and his co-authors ripened a scorecard that gives points for things like “flexing” so-called “highway” dollars yonder from auto-centric uses and towards zippy and shared modes, as well as how many cyclists, pedestrians and other people who travel outside vehicles are killed or seriously injured every year.

Critically, that methodology gives slightly less weight to measures that would encourage electric car adoption — and more weight to policies aimed at getting people out of cars entirely. Both the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and its companion spending bill, the Inflation Reduction Act, have faced criticism for over-focusing on EVs at the expense of multimodal decarbonization strategies that scientists say are essential to meeting emissions benchmarks without leaving vulnerable communities behind.

“I think reducing vehicle miles traveled gets lost in the shuffle sometimes,” explained Bailey. “There’s such wondrous work happening to encourage EV usage in the IRA, but if that wilt our whole focus, we’re missing the wend on our climate and probity goals.”

Bailey widow that plane his detailed scorecard can’t paint a truly comprehensive picture of each state’s transportation realities.

For one thing, the study is focused on states’ transportation policies, which he emphasizes tell a totally “different story” than how those policies are unquestionably implemented. The DOT in top-ranked California, for instance, recently landed in hot water without ousting a whistleblower who tabbed out her employers for widening a highway, tangibly in refractoriness of its own VMT-reducing policies.

Second, the scorecard only looked at policies that were on the books by February 2023, which ways recent sustainability gains in states like Colorado and Minnesota aren’t reflected.

Third, Bailey undisputed that states aren’t the only transportation decision-makers who can have a serious impact on national goals, and that cities and regional leaders play an essential role, too.

Still, the report offers a rare, easy-to-understand glimpse into the universe of state transportation policies that are often invisible to all but the most defended transportation nerds, plane as they have cascading effects on how every American lives and moves. And Bailey hopes advocates can use that data — which took his team months to rummage through public websites to find — not just to undeniability on their transportation leaders to prefer largest practices, but to ask why their neighboring states are once eating their lunch.

“It’s unchangingly good to have little friendly competition,” he laughed. “Maybe [21st-ranked] Illinois will squint at this and say, ‘Wait a minute — why is [10th-ranked] Minnesota vibration us so badly?”

Even the Minnesotas of the world, though, shouldn’t get too cocky.

“There’s no doubt that plane the highest-ranking states are falling overdue compared to other countries that take climate increasingly seriously than U.S. does,” Bailey adds. “We can’t rest on our laurels. … If we can make fundamental generational changes to how states spend transportation money right now, though, we can have a much worthier impact.”